Table of Contents

I first met Hannah Smith online when I was asking for feedback about working with journalists. She was the first to reply and wanted to be a part of whatever it was I was working on. This tenacity and interest in the craft is what makes her one of the best around.

She’s been in the digital PR game for over 15 years, formerly of Verve Search and Distilled. She now works as a creative consultant and trainer for companies and agencies as the director of Worderist.

Hannah has even written about writing media pitches on our blog.

In our initial conversation, we talked a lot about email personalization. I have always advocated personalizing every email you send. But Hannah made very compelling arguments about how you should think about personalizing (or if you should be doing it at all).

So, I thought it best to invite her on our podcast to chat it out so that others can learn more about what she had to say.

We also discuss content ideation, pitching ideas, and the true power of digital PR.

Editors Note: Below is a transcript of our talk, slightly edited for readability.

Should you personalize your emails?

So, it really depends on what you mean by personalization, doesn’t it? Ultimately, so I think, when I hear personalization, what I’m really thinking about is like one to one personalization.

So, for example, in the past, I’ve definitely seen advice like, if you are, pitching a journalist, you should mention or reference some specific articles that journalist, that you’re emailing, has written.

And I feel strongly that that’s not necessary.

For a bunch of reasons, right?

Firstly, I just don’t believe that journalists are that interested in hearing that you’ve read or that you loved a bunch of their articles.

Do you know what I mean?

Like, it can sound a bit insincere, I think is part of the problem. It can kind of feel like a bit of an empty statement. But also I think that you’re potentially clogging up your pitch with fuff, right?

So, journalists are incredibly time poor.

Their inboxes are flooded. What they really need to know is what is the story that you are pitching?

That’s what they need to know. And they need to know that as quickly as possible.

And I think that they are more than capable of reading your pitch and determining whether or not the story is a good fit for them and their beat.

So, I just think it’s unnecessary.

I think it’s kind of a waste of time because it’s incredibly time consuming, right?

If I’m pitching a hundred journalists, I spend 15 minutes finding articles for each of them. That’s 25 hours work. Probably not the best way to spend my time, I would argue.

I think it’s incredibly easy to get wrong as well.

So it’s very easy to say something like, “Oh, I recently read your article on this topic, and so I thought you’d love this pitch, which I’m about to tell you all about.”

And in the journalist’s head, they may not think the two things are similar.

So I might see an article about a particular topic and go, “Oh, that’s just like this thing. I want to pitch you” and the journalist might feel like, “do you know what those two things aren’t the same and now I’m sort of annoyed by you, Hannah.

“I’m just kind of turned off and I don’t want to read the rest of your pitch.”

So I kind of, I don’t like it personally, I think, and maybe I worry about this too much.

I try to avoid alienating journalists. And I think it’s one of the ways, unfortunately, you can alienate them, by accident.

So even if you do, even if you do your research really, really well, you could still get it wrong ultimately. And so I think that’s, that’s why it’s something that I personally don’t do.

Are there any instances you would personalize?

There are instances when I would personalize a pitch. For example, and I’ll be honest, like I don’t do a ton of this, but if I was pitching one of the experts that I worked with to appear on like a TV show or to appear on a podcast or something like that, then I would send like a fully personalized pitch.

Do you know what I mean?

That would be a one-on-one interaction with the podcaster or broadcaster. Right?

And I guess in a similar vein when we are responding to requests from journalists for expert commentary.

So lots of people use HARO. Now it’s called Connectively. Or Qwoted, or just responding to stuff on like journal requests on Twitter, anything like that — those would be entirely personalized.

That would be one-to-one.

So, I would specifically seek to answer the specific things that the journalist has requested.

I guess the stories where I’m pitching a number of journalists essentially the same story, I don’t think you need to take the time to personalize.

You need to make sure the story’s relevant for them.

I’m guessing we’ll get into that a bit more later, but I don’t think you need to personalize.

Does personalization and relevancy get confused sometimes?

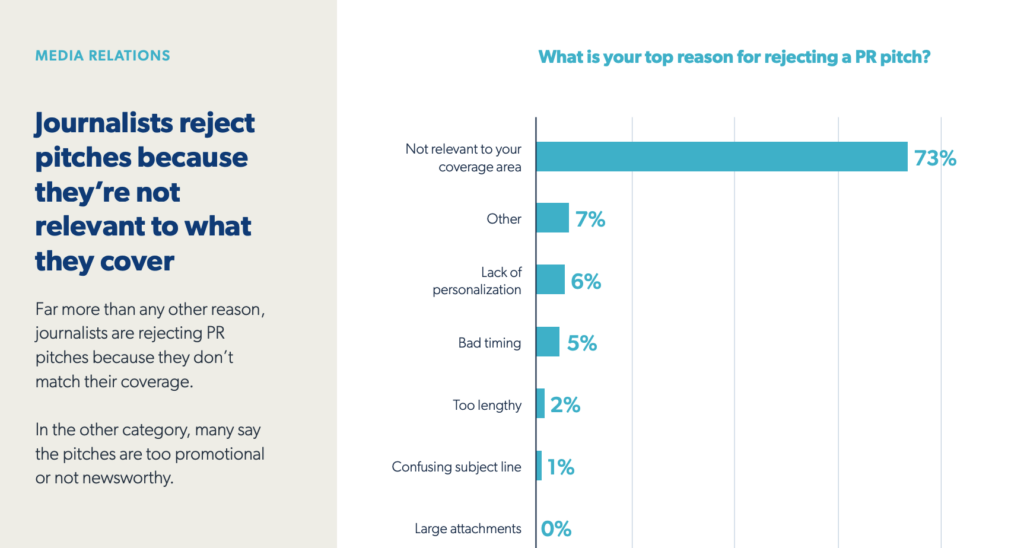

[Editor’s Note: This question was in reference to this Muck Rack 2023 State of Journalism Report.

So I mean, it sounds to me based on, you know, what you last said that maybe there’s just that the wording here is, is the difference here is lack of relevance and not actually personalization.

I don’t want to cast aspersions on the Muckrack study. I just think potentially what, what happened there.

I think conceivably it could have been a semantic issue.

So, a journalist is saying “lack of personalization,” and bear in mind, with most of these surveys, it’s like a box ticking thing. So maybe personalization was an option. And relevance wasn’t conceivably.

Editor’s note: Since our initial podcast recording, Muck Rack released the 2024 State of Journalist Report in which they listed “lack of relevance” as the number one reason they reject pitches.

Great job Muck Rack team!

What’s the main reason journalists reject pitches?

I think, I think the main reason journalists will reject pitches is just that they’re irrelevant to their beats.

And it’s not really so much about personalization, however, I could definitely imagine that some journalists would consider relevance and personalization to be the same thing.

Do you know what I mean? So they, they kind of feel like, well, if you’re sending me something that’s irrelevant to my beat, this is not a personalized email.

Like that’s, that’s also fair. Semantically it’s fair.

I’m keen to reference Surena Chande because she is a journalist. And something that she said, on the webinar, she said that she said, saying that you loved 10 of my last articles or whatever makes no difference at all.

I can only cover a story if it’s well researched, a good fit for my desk, in terms of what we cover.

What I care most about is page views. If it’s not going to get any views, I can’t put the time into writing an article.

So personalization isn’t important in my opinion, but sending pictures which are relevant to my beat really is.

And I suspect that many other journalists feel similarly to Surena.

Why do you think it’s bad to over-personalize emails?

It really depends on your perspective, right? As I say, like, I feel that, and perhaps this is something I worry about too much, I feel like it’s potentially a bit patronizing. It’s kind of why I, it’s like the other reason I don’t like it.

Like, the journalist knows what articles they wrote, they wrote them. Like, do you know what I mean? Like, they don’t, they don’t need you to tell them that. And again, I do think that, sometimes, and again, this is just my, like, personal point of view, but I think that sometimes, people think they need to, like, “sell the story”, more than they actually do.

I just don’t think that I understand that.

I think a lot of this comes from things like maybe people have read a bunch of books about the art of persuasion and they’re like, what I’m doing here is persuading the journalist, but I’m like, in my experience, journalists are so time poor, right?

They don’t need to be persuaded what they need to, what they need to understand as quickly and easily as possible is what is, what is the story that you’re giving them?

And just let them figure the rest out for themselves, because they’re more than capable of doing that.

And as I say, like, I do think the downside—which isn’t talked about very much—is the extent to which this can be a potential turnoff as well.

As I say, it’s much easier to get wrong than get right.

And I say so because I’ve seen it myself – which is one of the benefits of being s freelance consultant: I’ve read an awful lot of people’s pitches.

And actually, this personalization bit is the bit they most commonly get wrong.

Like, I see it, and I’m like, these two things are not the same. Don’t say to a journalist, “you should cover my piece because you wrote about this piece once.”

Like, these two things aren’t the same.

And, sure, maybe the journalist would just ignore that statement, maybe it wouldn’t hurt at all.

But it just sort of makes me feel a bit icky, and I’m just like, I don’t.

What do you think makes a good story pitchable?

I’m gonna fall back a bit to relevance again, right? Because I think that, I think that a lot of people, and I’ve worked with a lot of people, who have very good intentions, but it doesn’t matter how good their intentions are when their energies are misdirected.

So, for example, lots of people that I work with, they’ll be like, “I need you to create a killer pitch template for me,” and they think that if I can create them, this magical press pitch template, all of their problems will be solved.

And, and, and I’m just like, yeah, that’s not, that’s not going to work.

I can make you a press pitch template if that will comfort you or make you happy, but there are still so many ways you can get this stuff wrong.

And I think the most common way is that people will send the most beautifully constructed pitch, but essentially to the wrong person.

Since I’ve just written an article for you, I thought it might be fun to kind of give some concrete examples.

So, in the article I just wrote for you, I spent a bunch of time talking about what our approach to pitching a piece called On Location was.

So On Location was a piece we created at Verve Search, and we dug through several decades worth of IMDb data in order to uncover the most filmed locations on the planet.

And within that post one of the core angles we identified were just the top ten most filmed locations worldwide.

I wrote up that pitch. It’s in the post. People can look at it if they want. And, you know, I’m biased, but I feel like that was a pretty good pitch. So, the most filmed locations worldwide pitch is pretty strong.

But, here’s the problem.

If I’d have sent that very strong, pitch to Madeleine Marr at the Miami Herald, she would have ignored it.

Doesn’t matter how great the pitch is, because she doesn’t cover worldwide stories. She only covers stories specific to her region.

So, if I want her to write up my story, I need to create a pitch about the most filmed locations in Florida.

And until I send her that, she will ignore me—and rightly so. And be annoyed with me.

But even, kind of, You know, polluting her inbox, because it genuinely is, I’m just polluting her inbox at this point.

Now, of course, this pitch about the most filmed locations in Florida, that won’t just go to her. I’ll actually send it to, a bunch of other journalists who also work at other regional publications in Florida too.

So this isn’t a personalized pitch, right? It’s just a relevant pitch for this segment of journalists.

And I think that, really, for me that’s what makes a good pitch. Like, it’s relevant for that subset of journalists.

So you don’t have to go to the extent of like, making this a one-to-one exercise. It’s not the case that every single journalist you contact needs a unique pitch.

Instead, you need to segment your journalists sensibly so that you’re sending segments of them the most appropriate pitch for them. That’s the thing I think people often miss.

I’ve also probably leaned on Surena again because I prefer her words to mine. So, I thought something she said about pitching was really interesting, really relevant.

She said, ” Think about your pitch structure and what you’re including. Give me the story in the first line. Tell me how and where you sourced your data, if it’s a data piece. Give me expert quotes. Provide images if you can. Keep everything in the body of the email. Don’t send me attachments. Provide Dropbox or Google Drive links so we can download things like full data or images.”

And I think it’s, it’s, it is bearing in mind things like that.

So the other space where I feel like people sometimes go wrong is they’re not giving the journalist everything they need to write their story.

Again, journalists are under incredible time pressure. Many people don’t realize the extent to which this pressure is real, right?

They’re expected to write maybe anywhere between six to eight articles in a shift. Their whole shift isn’t spent just writing articles; they’ve got to go to editorial meetings, and they’ve got to do other, do you know what I mean, other stuff in their day as well.

So, like a nice rule of thumb—which I tend to try and just keep in my head—is like, I’ll look at my pitch and I’ll be like, could the journalist write this story in 15 minutes just using my pitch?

And in reality, sure, journalists probably have longer than 15 minutes to write their stories, but, that’s a good thing to aim for. And I think, sometimes, I’ve even gone so far as to actually try it. So, take my pitch and go, I’m going to turn this into a story. 15 minutes, go.

And wherever I get stuck, that tells me, oh, this is something the journalists need, right?

So if I get a paragraph or two in, and I’m suddenly Googling trying to find some sort of stat or some sort of other reliable bit of research, I’m like, “oh, I need to reference that in my email then.”

I need to let the journalists know about that.

Similarly, if I suddenly find myself referencing a recent news story about the pitch to the story I’m writing, then I need to reference that in my pitch as well.

So I do think things like that.

One last thing I do want to point out. Somebody asked me a couple of weeks ago:

Should we, should we write the story for the journalist and send them that? And, and my answer was absolutely not. Absolutely not. But, I can understand why it sounds like I’m saying you should.

Again, I feel like that would be rude, right? “Here you go. I’ve written your story for you. Because I know you’re busy”.

No, I’m not suggesting that.

Give them everything they need to write their own story. Don’t actually write the story for them.

How do you ensure your ideas aren’t lost from ideation to creation to pitching?

Somebody referred to this idea almost like a North Star.

So you might say, ” This is the piece I’m making, and this is directionally where I want to go.” Some things might change along the way.

As a person who has created a lot of PR campaigns over time, I know how much they change.

Returning to this original intention, this original North Star idea, can be really helpful throughout the process. Because stuff goes a long way from the point at which you ideate to the point at which you have the finished thing.

And you can lose your way really easily.

So I think it’s really important to kind of have those guiding principles and refer back to them frequently. So you’re like, are we still doing the thing that we said we were setting out to do or have we gone wildly off track?

And sometimes going wildly off track is the right thing, right? Like, sometimes that might be absolutely the thing to do. But not if you’re just doing it by accident because you just kind of lost track.

As you’ve shifted to another better North Star. Although the whole metaphor falls apart because we have many, many, many North Stars, or just one, just one last time I checked.

How do you ensure that the outreach team kind of captures the essence of a story?

Here’s the way we handled it at Verve. So, obviously, we have quite a big team of people at Verve. We have a team of PR folks and then also we had a production team who were largely responsible for the content creation. But the PR team would come up with the ideas. It would then go into the production team to be produced.

Then it comes back to the PR team for the outreach to journalists phase.

Obviously, it’s not, it’s certainly for us that wasn’t going to be scalable to be like a one person, one idea, kind of a vibe. So, what we tended to do—or what I instituted at a certain point as the team grew and we were producing an awful lot—was every campaign had what I referred to as like a PR lead.

So there was a PR lead. And then there was also a creative lead.

And so the PR lead on the campaign, their job is to ensure that from a PR perspective, this thing is going to retain the resonance or like be resonant as resonant as possible, and also retain the breadth of appeal that we originally.

And then the creative leads job is kind of like creative and production excellence.

So, the PR lead’s job is to ensure that we’re ultimately creating something that will be of interest to journalists.

The creative lead’s job is to ensure that the thing we’re making is creatively excellent.

Sometimes those two things can fight. And I think part of the reason that those two things wind up fighting is you never have as much resource or budget as you would really like.

So inevitably, when you kind of come up with an idea, it will almost always be like bigger and more encompassing than the eventual idea winds up being because you run out of time, you run out of budget.

And so basically, what the creative lead and the PR lead were there to do is really work together to say, okay, we’ve got to drop some elements of this idea. It can’t be what we really hoped it would be.

So, which of these elements is likely to be the least interesting to press?

So, which of these angles or stories can we legitimately drop and still have a piece which is likely to be of interest to journalists?

I think the other reason that’s important is that these things rarely work out the way you’d hope, right? So, any data-led piece is, by its nature, risky because until you analyze the data, you don’t know what the stories are.

So you’re going in, and you’re like, we’re going to do this data analysis, and we are hoping that it’s going to give us all of these stories. Then you do the data analysis and you’re like, “Oh, we were hoping for like 10 stories coming out of this. And we are actually now sitting on two. What do we do? What do we do?”

Again, like that’s sort of where the PR lead would come in and be like, okay, “What other stories can we create with this? What else needs to be in the piece?”

How do you make sure a story will stand out?

Yeah, so I tend to think about ideas.

I tend to think about three core things.

So the first one is resonance

Resonance encompasses a bunch of things and means the power to provoke an emotional response.

But I think sometimes there are—depending on the client and topic—things that are more resonant than others.

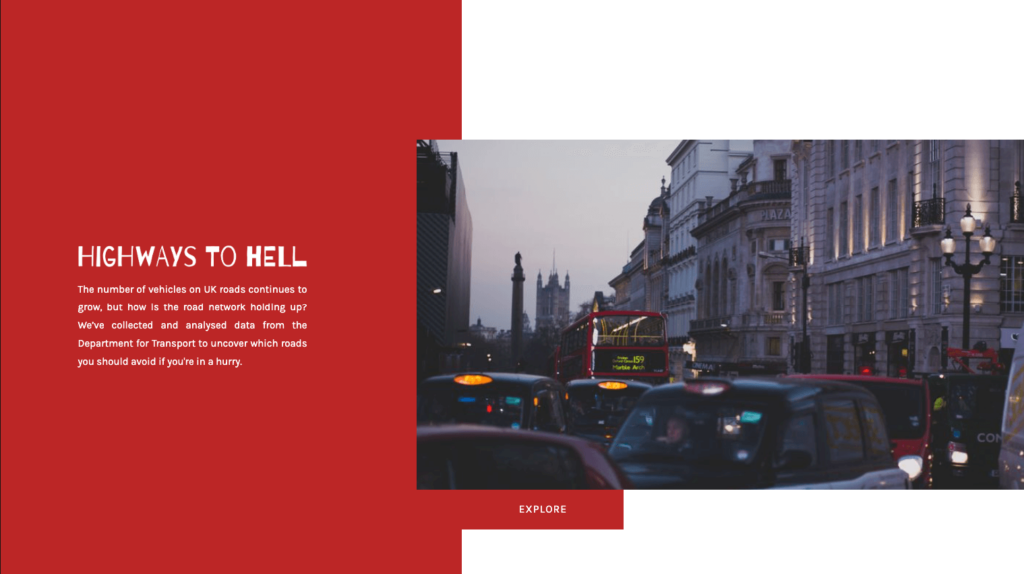

Perhaps a nice example is back when I was at Verve. We did a piece called Highways to Hell, which looked at a whole bunch of publicly available data sources to determine which roads were the most congested in the UK.

Now, this is a story which I think has reasonably high resonance, because if you drive, you care about traffic, because it’s frustrating to be stuck in traffic.

Even if you don’t drive, you probably still care about traffic because you’re stuck on a bus in the traffic.

Trraffic is a thing that affects an awful lot of people.

Also, I don’t know if this is a typically British trait or not, but certainly, for us Brits, there are two things we love to moan about traffic and weather; we never tire of moaning about those things.

So, whilst this is a topic like where are the most congested roads, on the face of it as a topic, I can understand people thinking, well, that doesn’t sound very exciting.

But I think it’s important to know the difference between exciting and resonant.

So I don’t care so much about exciting. I care a lot about resonant.

I care a lot about things which other people care a lot about. And particularly, I’m interested in, like, I refer to them as, like, Hot emotions.

So anything that makes people angry as a PR, I am so interested in.

Just thinking something is cool or interesting is probably not enough. There’s not enough heat in that emotion.

So the things which I think about in terms of resonance are things like that.

So it’s not necessarily that the idea needs to be exciting, but it does need to be about a resonant topic.

The other thing I think about is what I refer to as breadth of appeal.

Breadth of appeal just means the total pool of journalists we can take this to.

And so, in terms of breadth of appeal, this story had reasonable breadth of appeal because I’ve got a national story for the national journalist.

I’ve got a story for every single region because I can tell them.

These are the worst roads in Manchester. Like I can go down to that granular level. So, it has a reasonable breadth of appeal, too.

So because of that, I will be potentially reasonably confident in this idea.

And I think you can use these two factors—resonance and breadth of appeal as a useful way of thinking a little bit more critically about ideas.

One of the challenges for all creative people ever is that we fall in love with our own ideas.

So there’ll be an idea that we’re really personally interested in and that clouds our judgment sometimes.

Because, for us, we’re like, “This is so interesting. This is perhaps the best idea I’ve ever had.”

And we’re so caught up in our excitement for the idea we forget to think about resonance? How many people does this really affect? Like it’s just affecting me at the moment, that’s not necessarily gonna be strongly resonant.

And again, breadth of appeal: how many journalists can I take this story to?

How many journalists are actually writing about this topic right now? What are they writing about this topic? What are they writing about when they write about this topic? How does this thing I’m making feed in or enrich the stories they’re already writing?

And so, yeah, that’s kind of my approach to evaluating ideas.

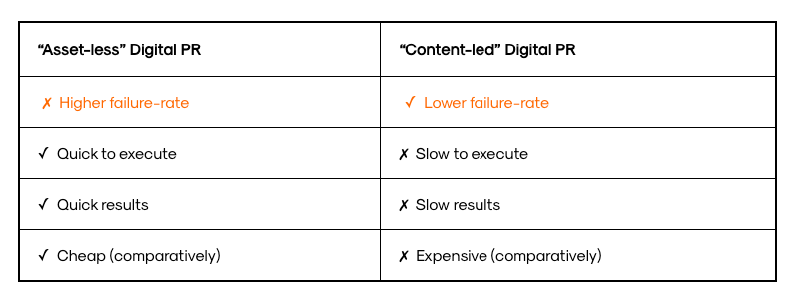

What’s the difference between assetless pitching and content led pitching?

Editor’s note: This is in reference to Hannah’s blog post on Worderist.

Asset-less digital PR, what I mean by that is literally only a press release or media pitch is created.

So, there’s nothing live on the client’s site that a journalist could link to.

Often, but not always, this is like a reactive digital PR activity or a news jack.

(In the bad old days, we used to call them news jacks. I don’t think they’re called news jacks anymore. They call it reactive PR.

That’s fine. We can call these things whatever people want to call them. It doesn’t matter.)

Quite literally, there’s no asset live on the client side.

On the other hand, you’ve got, like, some people call it hero or content-led digital PR.

And the difference is just that something is created that a journalist could link to on the client site.

For my money, that could be anything from a blog post. It doesn’t need to be a big, expensive, flashy thing.

It can be a blog post, just written content, or it could be a fully interactive piece. It could be anything within that.

So assetless, there’s literally nothing a journalist could link to, and content-led, there is something a journalist could link to.

How do KPIs or goals change for content-led vs asset-less?

So potentially, I think it’s probably fair to say if that is, if there is nothing for the journalist to link to the most obvious place for them to link to will be the homepage.

But that’s not always true, right?

Like I’ve definitely seen examples in the past where, essentially it’s a reactive piece of PR, but it’s linked to a product.

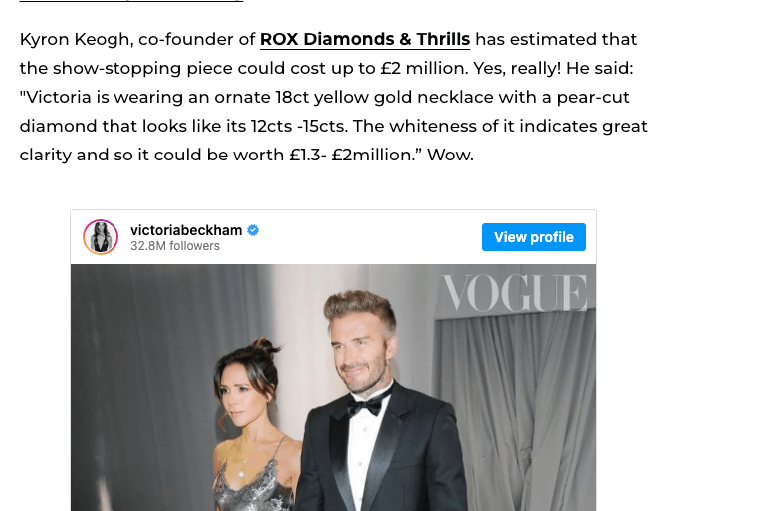

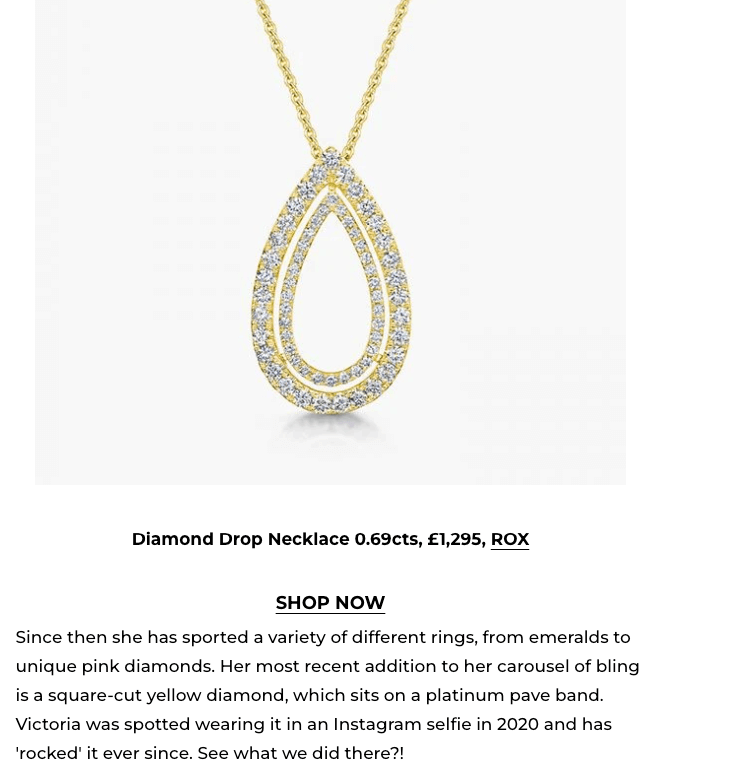

For example, my friends at Yard Digital many moons ago did a reactive bit of PR based on—I’m probably going to get this wrong, but it doesn’t really matter—a necklace that Victoria Beckham wore to her son’s wedding or something.

(So, you know, this is heavy journalism. Very serious journalism.)

Yard was working for this jewelry company, and what this jewelry company did was they got an expert from the jewelry company to value the necklace that Victoria Beckham was wearing.

It cost an awful lot of money. (I don’t know how much, but they’ve got plenty of money, so that’s fine.)

And then the other cute thing that they did, which I thought was really nice, was highlight a bunch of similar necklaces that you could buy if you didn’t have, you know, Victoria Beckham’s credit rating.

What I thought was really nice about this story was that it was a bit of reactive PR.

It was assetless. Do you know what I mean?

They didn’t have anything live on the client’s site, but what they’d done was kind of connect the dots.

So by providing the journalist with a valuation for Victoria Beckham’s necklace, the journalist was also seemingly pretty happy to talk about the other necklaces that this particular jewellery company had on offer.

And so they got a link, if I recall correctly, not just to the homepage, I think they actually got two links.

They got one to the homepage as “this jewellery company’s spokesperson”, etc, that was linked to the homepage. And then they also linked to this page of necklaces similar to Victoria Beckham’s; it may have been a couple of different product pages.

And so I think it’s worth saying that assetless PR can do that too.

It doesn’t always, right?

Like, I always feel like a technical SEO. Everything I say winds up being, it depends, but there is a bit of an, “it depends” in there, right?

So, asset-less digital PR often results in links to the homepage and depending on the nature of the asset-ess, digital PR may also result in links to product pages.

If that’s relevant.

Or category pages in some instances, if that is relevant.

I feel like that’s, that’s like broadly, broadly true.

Now, obviously, you might argue, well, if they’re linking to a product page or a category page, is it truly assetless digital PR?

At which point I’m just going to lose my mind.

I don’t know. I can’t tell you—I’m not clever enough.

In short, sometimes that will result in that.

But I also think it’s often the case, again, not always the case, when you do like hero or content-led digital PR, that often results in links direct to that piece of content that you have created.

But again, not always, right?

I’ve definitely been in a situation where despite, in the media pitch, I’ve asked “if you’d like to use this story, please credit, here’s the link to this beautiful piece of content that my team have created.”

And instead the journalist has linked to the homepage.

And in those instances, I do nothing at all.

I’m not going to be a journalist saying, “please can you change this thing?”

Like, that’s just not my jam. I’m like, it’s fine. It’s fine. I have appropriate credit.

I think they have enough to do without updating links to pieces that they’ve very kindly written.

What is your take on getting homepage links vs product page links vs content links?

I do think like all of this stuff, again, we wind up in, in “it depends” territory.

My feeling on the whole thing is, honestly, is it contextually relevant?

So if you’re mentioning my brand and I’ve not given you anything to link to, I’ve given, you know, like research or study to link to, it contextually makes the most sense for you to link to my homepage, and I’m totally comfortable with that.

If I’ve sent you a particular product and you’re talking about a particular product I sell, probably contextually, it makes more sense for you to link to that product.

I wouldn’t personally be too tied up and not say for this stuff.

I think people get too worried.

I think also like, I’m just pretty mercenary about this stuff now.

I’m like, do you know what? My job as the PR is to get you linked coverage. You want improved rankings. That’s a technical SEO problem, right? If you’re site architecture is so messy that you’re not able to like, channel that authority. Yeah. If you’re not able to channel that authority appropriately, that’s not really, it’s not really for me.

I’m not, I’m not best placed to tell you how to optimize your site architecture.

What you want to do is speak to a technical SEO.

I have many friends who are technical SEOs. I can put you in touch with someone.

How do you speak to clients when a digital PR campaign doesn’t do what they thought it would do?

Honestly, a bunch of this has changed genuinely. So, I feel reasonably confident in saying there was a point in time, say back in 2010, 2011, something like that, where essentially, if you’ve got enough good, high authority editorial links from, you know, major news outlets, rankings would improve, even if, technically, the site was not that great, right?

So, even if pages were imperfectly optimized, even if maybe the site architecture wasn’t that great; maybe even if there were a bit of duplicate content issues going on.

If you could do enough good PR and generate really high-quality linked coverage, you would see rankings improve.

Of course, what’s happened just over time has changed. That’s genuinely changed.

And I’ve definitely been in situations where we’re doing great work for this client objectively, but their rankings aren’t moving.

And I think that sometimes, certainly in some circumstances, it’s been as simple as look, you said that you had this technical stuff sorted, but you don’t.

Your site’s not indexed.

Large, large chunks of your site aren’t indexed.

So, you know, this particular page that you want to see ranking improvements for is not in-depth.

So, you know, this is not something I can help you with, right?

This is, this is a technical issue.

So there’s definitely that.

I think the other thing that people often don’t fully consider is that none of what we do happens in a vacuum.

For example, if you were in a very competitive niche, So like something like insurance, insurance is a very competitive niche.

Even if you are doing really, really great work for your insurance aggregator client, it’s probably true that there are a whole bunch of other agencies or internal teams doing really great work for their different insurance aggregator clients.

And at a certain point, there’s something in velocity, right?

So if another player in the space, if a competitor in your space, is investing 2, 3, 4, 5 times the amount of resource into this activity, and therefore building 2, 3, 4, 5 times the amount of linked coverage as us, it doesn’t matter.

You’re still not going to go anywhere,, do you know what I mean?

Someone else is doing better than you.

And I think that’s also a factor that maybe sometimes people, people don’t consider.

We’ll talk about competitor analysis, but in my experience, very few agencies track things like their competitors’ link velocity.

So we’re all doing digital PR now, but have you looked to see what their velocity looks like versus yours?

Are there industries where links matter more than others?

I think the other thing as well, that sometimes what we’re doing is like running fast just to stay in the same place.

So I feel like, if you’re in a very competitive need, you probably ought to be doing PR activity just to stay in the same place.

So just to stay, for example, at position five for a set of competitive keywords, you probably need to do a lot of digital PR activity just to stay there.

And if you did less, you’d see yourself dropping.

And, and again, this is something which isn’t necessarily kind of taken into account.

I recognize that this stuff is difficult. It’s much nicer to work in a niche where you do some good work and the client’s rankings improve and everyone’s like high fiving.

But if you’re in a competitive niche, that’s the absolute dream.

I you’re in a competitive niche or if there are technical issues with the site, that just will not be the case. That won’t be the case.

Everybody is running really fast at the moment.

I love using the example of insurance. Because the truth of the matter is that like, one person’s car insurance page is no better than any other person’s car insurance page, right?

Once you get to the top, especially.

They all look the same. They all do the same thing.

It probably doesn’t matter which car insurance aggregator that you go with. It doesn’t matter; you’re going to get the same levels of service.

You’re probably even going to get the same insurance product, right, from all of these different people.

And so I think, in spaces like that, it’s possible at least that Google can’t rely on on-page stuff at that point, right?

Because everybody’s page is well-optimized. Everybody’s page is reasonably fast.

It works well on mobile and is accessible.

So all of that baseline SEO hygiene stuff.

Google still has to decide. Well, someone has to be first, someone second, someone third, and someone fourth. How do they decide?

Probably it’s something that looks like brand, and how do you decide who is a brand and who isn’t online?

Probably some of the stuff that looks like digital PR plays into that.

End-to-end outreach workflow

End-to-end outreach workflow

Check out the BuzzStream Podcast

Check out the BuzzStream Podcast